Vincent Van Gogh

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

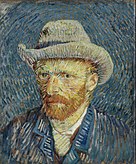

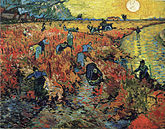

Vincent Willem van Gogh (Dutch: [ˈvɪnsənt ˈʋɪləm vɑŋ ˈɣɔx] (About this soundlisten);[note 1] 30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch post-impressionist painter who posthumously became one of the most famous and influential figures in the history of Western art. In a decade, he created about 2,100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings, most of which date from the last two years of his life. They include landscapes, still lifes, portraits and self-portraits, and are characterised by bold colours and dramatic, impulsive and expressive brushwork that contributed to the foundations of modern art. He was not commercially successful, and his suicide at 37 came after years of mental illness, depression and poverty. Born into an upper-middle-class family, Van Gogh drew as a child and was serious, quiet, and thoughtful. As a young man he worked as an art dealer, often travelling, but became depressed after he was transferred to London. He turned to religion and spent time as a Protestant missionary in southern Belgium. He drifted in ill health and solitude before taking up painting in 1881, having moved back home with his parents. His younger brother Theo supported him financially, and the two kept a long correspondence by letter. His early works, mostly still lifes and depictions of peasant labourers, contain few signs of the vivid colour that distinguished his later work. In 1886, he moved to Paris, where he met members of the avant-garde, including Émile Bernard and Paul Gauguin, who were reacting against the Impressionist sensibility. As his work developed he created a new approach to still lifes and local landscapes. His paintings grew brighter in colour as he developed a style that became fully realised during his stay in Arles in the south of France in 1888. During this period he broadened his subject matter to include series of olive trees, wheat fields and sunflowers. Van Gogh suffered from psychotic episodes and delusions and though he worried about his mental stability, he often neglected his physical health, did not eat properly and drank heavily. His friendship with Gauguin ended after a confrontation with a razor when, in a rage, he severed part of his own left ear. He spent time in psychiatric hospitals, including a period at Saint-Rémy. After he discharged himself and moved to the Auberge Ravoux in Auvers-sur-Oise near Paris, he came under the care of the homeopathic doctor Paul Gachet. His depression continued and on 27 July 1890, Van Gogh shot himself in the chest with a Lefaucheux revolver.[6] He died from his injuries two days later. Van Gogh was unsuccessful during his lifetime, and he was considered a madman and a failure. He became famous after his suicide and exists in the public imagination as a misunderstood genius, the artist "where discourses on madness and creativity converge".[7] His reputation began to grow in the early 20th century as elements of his painting style came to be incorporated by the Fauves and German Expressionists. He attained widespread critical, commercial and popular success over the ensuing decades, and he is remembered as an important but tragic painter, whose troubled personality typifies the romantic ideal of the tortured artist. Today, Van Gogh's works are among the world's most expensive paintings to have ever sold, and his legacy is honoured by a museum in his name, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which holds the world's

Letters

The most comprehensive primary source on Van Gogh is the correspondence between him and his younger brother, Theo. Their lifelong friendship, and most of what is known of Vincent's thoughts and theories of art, are recorded in the hundreds of letters they exchanged from 1872 until 1890.[8] Theo van Gogh was an art dealer and provided his brother with financial and emotional support as well as access to influential people on the contemporary art scene.[9] Theo kept all of Vincent's letters to him;[11] Vincent kept few of the letters he received. After both had died, Theo's widow Johanna arranged for the publication of some of their letters. A few appeared in 1906 and 1913; the majority were published in 1914.[12][13] Vincent's letters are eloquent and expressive and have been described as having a "diary-like intimacy",[9] and read in parts like autobiography.[9] The translator Arnold Pomerans wrote that their publication adds a "fresh dimension to the understanding of Van Gogh's artistic achievement, an understanding granted to us by virtually no other painter".[14]

There are more than 600 letters from Vincent to Theo and around 40 from Theo to Vincent. There are 22 to his sister Wil, 58 to the painter Anthon van Rappard, 22 to Émile Bernard as well as individual letters to Paul Signac, Paul Gauguin and the critic Albert Aurier. Some are illustrated with sketches.[9] Many are undated, but art historians have been able to place most in chronological order. Problems in transcription and dating remain, mainly with those posted from Arles. While there Vincent wrote around 200 letters in Dutch, French and English.[15] There is a gap in the record when he lived in Paris as the brothers lived together and had no need to correspond.[16] The highly paid contemporary artist Jules Breton was frequently mentioned in Vincent's letters. In 1875 letters to Theo, Vincent mentions he saw Breton, discusses the Breton paintings he saw at a Salon, and discusses sending one of Breton's books but only on the condition that it be returned.[17] [18] In a March 1884 letter to Rappard he discusses one of Breton's poems that had inspired one of his own paintings.[19] In 1885 he describes Breton's famous work The Song of the Lark as being "fine".[20] In March 1880, roughly midway between these letters, Van Gogh set out on an 80 kilometer trip on foot to meet with Breton in the village of Courrières, however, he was apparently intimidated by Breton's success and/or the high wall around his estate. He turned around and went back without making his presence known.[21][22] [23] It appears Breton was unaware of Van Gogh or his attempted visit. There are no known letters between the two artists and Van Gogh is not one of the contemporary artists discussed by Breton in his 1891 autobiography Life of An Artist.

Life

Early years

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on 30 March 1853 in Groot-Zundert, in the predominantly Catholic province of North Brabant in the Netherlands.[24] He was the oldest surviving child of Theodorus van Gogh (1822–1885), a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, and his wife Anna Cornelia Carbentus (1819–1907). Van Gogh was given the name of his grandfather and of a brother stillborn exactly a year before his birth.[note 2] Vincent was a common name in the Van Gogh family: his grandfather, Vincent (1789–1874), who received a degree in theology at the University of Leiden in 1811, had six sons, three of whom became art dealers. This Vincent may have been named after his own great-uncle, a sculptor (1729–1802).[26]

Van Gogh's mother came from a prosperous family in The Hague,[27] and his father was the youngest son of a minister.[28] The two met when Anna's younger sister, Cornelia, married Theodorus's older brother Vincent (Cent). Van Gogh's parents married in May 1851 and moved to Zundert.[29] His brother Theo was born on 1 May 1857. There was another brother, Cor, and three sisters: Elisabeth, Anna, and Willemina (known as "Wil"). In later life Van Gogh remained in touch only with Willemina and Theo.[30] Van Gogh's mother was a rigid and religious woman who emphasised the importance of family to the point of claustrophobia for those around her.[31] Theodorus's salary was modest, but the Church supplied the family with a house, a maid, two cooks, a gardener, a carriage and horse, and Anna instilled in the children a duty to uphold the family's high social position.[32]

Van Gogh was a serious and thoughtful child.[33] He was taught at home by his mother and a governess and in 1860 was sent to the village school. In 1864, he was placed in a boarding school at Zevenbergen,[34] where he felt abandoned, and he campaigned to come home. Instead, in 1866 his parents sent him to the middle school in Tilburg, where he was deeply unhappy.[35] but do not approach the intensity of his later work.[37] Constant Cornelis Huijsmans, who had been a successful artist in Paris, taught the students at Tilburg. His philosophy was to reject technique in favour of capturing the impressions of things, particularly nature or common objects. Van Gogh's profound unhappiness seems to have overshadowed the lessons, which had little effect.

In July 1869 Van Gogh's uncle Cent obtained a position for him at the art dealers Goupil & Cie in The Hague.[40] After completing his training in 1873, he was transferred to Goupil's London branch on Southampton Street and took lodgings at 87 Hackford Road, Stockwell.[41] This was a happy time for Van Gogh; he was successful at work and, at 20, was earning more than his father. Theo's wife later remarked that this was the best year of Vincent's life. He became infatuated with his landlady's daughter, Eugénie Loyer, but was rejected after confessing his feelings; she was secretly engaged to a former lodger. He grew more isolated and religiously fervent. His father and uncle arranged a transfer to Paris in 1875, where he became resentful of issues such as the degree to which the firm commodified art, and he was dismissed a year later.

Etten, Drenthe and The Hague

Van Gogh returned to Etten in April 1881 for an extended stay with his parents.[62] He continued to draw, often using his neighbours as subjects. In August 1881, his recently widowed cousin, Cornelia "Kee" Vos-Stricker, daughter of his mother's older sister Willemina and Johannes Stricker, arrived for a visit. He was thrilled and took long walks with her. Kee was seven years older than he was and had an eight-year-old son. Van Gogh surprised everyone by declaring his love to her and proposing marriage.[63] She refused with the words "No, nay, never" ("nooit, neen, nimmer").[64] After Kee returned to Amsterdam, Van Gogh went to The Hague to try to sell paintings and to meet with his second cousin, Anton Mauve. Mauve was the successful artist Van Gogh longed to be.[65] Mauve invited him to return in a few months and suggested he spend the intervening time working in charcoal and pastels; Van Gogh went back to Etten and followed this advice.[65]

Late in November 1881, Van Gogh wrote a letter to Johannes Stricker, one which he described to Theo as an attack.[66] Within days he left for Amsterdam.[67] Kee would not meet him, and her parents wrote that his "persistence is disgusting".[68] In despair, he held his left hand in the flame of a lamp, with the words: "Let me see her for as long as I can keep my hand in the flame."[68][69] He did not recall the event well, but later assumed that his uncle had blown out the flame. Kee's father made it clear that her refusal should be heeded and that the two would not marry, largely because of Van Gogh's inability to support himself.[70]

Mauve took Van Gogh on as a student and introduced him to watercolour, which he worked on for the next month before returning home for Christmas.[71] He quarrelled with his father, refusing to attend church, and left for The Hague.[note 5][72] In January 1882, Mauve introduced him to painting in oil and lent him money to set up a studio.[73][74] Within a month Van Gogh and Mauve fell out, possibly over the viability of drawing from plaster casts.[75] Van Gogh could afford to hire only people from the street as models, a practice of which Mauve seems to have disapproved.[76] In June Van Gogh suffered a bout of gonorrhoea and spent three weeks in hospital.[77] Soon after, he first painted in oils,[78] bought with money borrowed from Theo. He liked the medium, and he spread the paint liberally, scraping from the canvas and working back with the brush. He wrote that he was surprised at how good the results were.[79]

Style and works

Artistic development

Van Gogh drew, and painted with watercolours while at school, but only a few examples survive and the authorship of some has been challenged.[217] When he took up art as an adult, he began at an elementary level. In early 1882, his uncle, Cornelis Marinus, owner of a well-known gallery of contemporary art in Amsterdam, asked for drawings of The Hague. Van Gogh's work did not live up to expectations. Marinus offered a second commission, specifying the subject matter in detail, but was again disappointed with the result. Van Gogh persevered; he experimented with lighting in his studio using variable shutters and different drawing materials. For more than a year he worked on single figures – highly elaborate studies in black and white,[note 11] which at the time gained him only criticism. Later, they were recognised as early masterpieces.[219]

In August 1882 Theo gave Vincent money to buy materials for working en plein air. Vincent wrote that he could now "go on painting with new vigour".[220] From early 1883 he worked on multi-figure compositions. He had some of them photographed, but when his brother remarked that they lacked liveliness and freshness, he destroyed them and turned to oil painting. Van Gogh turned to well-known Hague School artists like Weissenbruch and Blommers, and he received technical advice from them as well as from painters like De Bock and Van der Weele, both of the Hague School's second generation.[221] When he moved to Nuenen after the period in Drenthe he began several large paintings but destroyed most of them. The Potato Eaters and its companion pieces are the only ones to have survived.[221] Following a visit to the Rijksmuseum, Van Gogh wrote of his admiration for the quick, economical brushwork of the Dutch Masters, especially Rembrandt and Frans Hals.[222][note 12] He was aware that many of his faults were due to lack of experience and technical expertise,[221] so in November 1885 he travelled to Antwerp and later Paris to learn and develop his skills.[223]

Van Gogh strove to be a painter of rural life and nature,[230] and during his first summer in Arles he used his new palette to paint landscapes and traditional rural life.[231] His belief that a power existed behind the natural led him to try to capture a sense of that power, or the essence of nature in his art, sometimes through the use of symbols.[232] His renditions of the sower, at first copied from Jean-François Millet, reflect Van Gogh's religious beliefs: the sower as Christ sowing life beneath the hot sun.[233] These were themes and motifs he returned to often to rework and develop.[234] His paintings of flowers are filled with symbolism, but rather than use traditional Christian iconography he made up his own, where life is lived under the sun and work is an allegory of life.[235] In Arles, having gained confidence after painting spring blossoms and learning to capture bright sunlight, he was ready to paint The Sower.[226]

Van Gogh stayed within what he called the "guise of reality",[236] and was critical of overly stylised works.[237] He wrote afterwards that the abstraction of Starry Night had gone too far and that reality had "receded too far in the background".[237] Hughes describes it as a moment of extreme visionary ecstasy: the stars are in a great whirl, reminiscent of Hokusai's Great Wave, the movement in the heaven above is reflected by the movement of the cypress on the earth below, and the painter's vision is "translated into a thick, emphatic plasma of paint".[238] Between 1885 and his death in 1890, Van Gogh appears to have been building an oeuvre,[239] a collection that reflected his personal vision and could be commercially successful. He was influenced by Blanc's definition of style, that a true painting required optimal use of colour, perspective and brushstrokes. Van Gogh applied the word "purposeful" to paintings he thought he had mastered, as opposed to those he thought of as studies.[240] He painted many series of studies;[236] most of which were still lifes, many executed as colour experiments or as gifts to friends.[241] The work in Arles contributed considerably to his oeuvre: those he thought the most important from that time were The Sower, Night Cafe, Memory of the Garden in Etten and Starry Night. With their broad brushstrokes, inventive perspectives, colours, contours and designs, these paintings represent the style he sought.[237]